I’ve been back from Scotland for way too long. Almost six weeks. Don’t get me wrong, I am fortunate to have great friends, a home I love and fulfilling work. I live in a beautiful mountainous place steeped in outdoor culture. Literally everyone is moving here (looking at you Californians). For the record, I’m extremely lucky. Even so, I feel the gentle pull of a Scottish tractor beam (sorry, reading Patrick Stewart’s delightful bio) and it feels sustaining, like a program running in the background. I’m returning in May but honestly this seems like an age away. And as it happens there’s a Scottish Gaelic word expressing this feeling exactly. There is no English translation.

The word is cianalas, something I’ve written about before. It is a deep-seated sense of belonging to the place where your roots lie, or where you feel profoundly at home. It’s a feeling that you are exactly where you need to be in the world, a feeling that runs right down to your toes and causes you to smile idiotically while hiking across a moor alone in the fog, wind and driving rain. It’s a place that dampens anxiety and worry and offers more zen than an hour of meditation. Cianalas is longing for the place you belong. At the (very high) risk of sounding impossibly cheesy and naive, there it is.

(Tonal shift warning for a brief PSA: to avoid annoying Scots, Gaelic is pronounced with a short “a” like “apple” – the perhaps more familiar pronunciation with a long “a” like “table” refers to Irish Gaelic – same roots, different language.)

So after that bit of schmaltzy waxing poetical, let’s rejoin our regularly scheduled programming and return to the Outer Hebrides, which is where the word cianalas actually originated. Our merry band of Wilderness Scotland travelers stayed at the lovely Harris Hotel in Tarbert. As Harris is the most mountainous area of the single landmass of Harris and Lewis, we planned to spend most of our hiking time there. Harris and Lewis combined are the largest island in Scotland with a population of about 21,000, and the important thing to remember is that most of them are MacLeods.

Our first day of walking featured more awesomely bad weather! We drove across a little bridge to another island southeast of Harris called Scalpay, and enjoyed a very rainy walk to Eilean Gas, one of the first four lighthouses to be built in Scotland. It looks back across the Minch toward Skye, so awesome views when it’s not all fogged in. It was built by Robert Stevenson in 1789 and became fully automated in 1978. Robert and his descendants designed and built basically all of Scotland’s lighthouses over a 150-year period. As we know, the black sheep of that family happened to be Robert Louis Stevenson, and our guide Liam shared how much he enjoyed imagining young Robert sitting off to one side, completely bored by all this tedious lighthouse whatever business, scribbling in a notebook and generally being a terrible disappointment to his family. Liam clearly saw RLS as a kindred spirit.

The grounds are pretty cool to wander about, with barracks and other associated buildings. If you happen to be there during high season, there’s even a coffee shop with views over the sea. I stared longingly through the windows at the espresso machine as a wee shot would have been just the thing on the cold wet day. “There’s an espresso machine in there, ” I told everyone, alas, to no avail.

Here’s a cool thing. We happened to be visiting on the 234th anniversary of the original lighting of the lamp.

Liam told a story that I haven’t been able to confirm and that he might have conflated with another tale of a different Hebridean lighthouse, and so I’m going to share both as they are equally creepily awesome. He explained that two families once lived at Eilean Glas and their job was to operate the lighthouse – it was very remote, no roads, and so the families had to be self-sustaining by growing their own food and so on. Apparently there were reports that the lamp hadn’t been lit for a few days, and so a crew was dispatched to investigate. They found food on the table and other signs of a sudden disappearance – and not a single family member remained, nor was anyone ever found. This got my mind spinning about writing a novel based on this unsolved mystery – I mean c’mon it’s basically an X-File and practically writes itself. So, when I got home, I did some googling.

The (rather well-known, actually) story I found involved the sudden disappearance of three men at the Eilean Mor lighthouse in the Flannen Islands about 32 miles west of Lewis. On December 26, 1900, a small ship arrived on shore, bringing a replacement lighthouse keeper, Joseph Moore. Strangely, nobody was at the landing platform to greet them, so Moore walked up the hill to the lighthouse. He noticed something was immediately sketchy as its door was unlocked and two of the three oilskin coats were missing from the entrance hall. In the kitchen Moore found half-eaten food and an overturned chair as if someone had jumped from their seat. And (whispers) the kitchen clock had stopped.

The men were never found, although there were some strange recent log entries. On December 12, Thomas Marshall, the second assistant, wrote of “severe winds the likes of which I have never seen before in twenty years.” Marshall also noted that James Ducat, the Principal Keeper, had been “very quiet” (serial killer alert!) and that the third assistant, William McArthur, a seasoned mariner and known as a “tough brawler,” had been crying. So maybe the quiet one lost his mind due to the alleged high winds and maybe the crying, killed the other two and tossed them into the ocean, and wandered off into the mist and over a cliff.

I say “alleged” because a later investigation by British authorities revealed that there were no reported storms in the area at that time. The weather was calm.

Maybe all three of them got drunk, went for a walk and took a pratfall into the sea at the same time, maybe it was a sea monster (amateur sleuths at the time really considered this), or it could have had something to do with the islands’ namesake St. Flannen. He was a 6th century Irish Bishop who later became a saint. He built a chapel on the island (the lighthouse keepers called it the “dog kennel” due to its size which possibly wasn’t great karma) and for centuries shepherds used to bring sheep to graze nearby but refused to sleep over due to reported haunty spirits.

Nobody has lived on the Flannen Islands since 1971, when the lighthouse became automated. I wonder if Moore stayed behind to operate the place or if he suffered a debilitating case of the willies and retired.

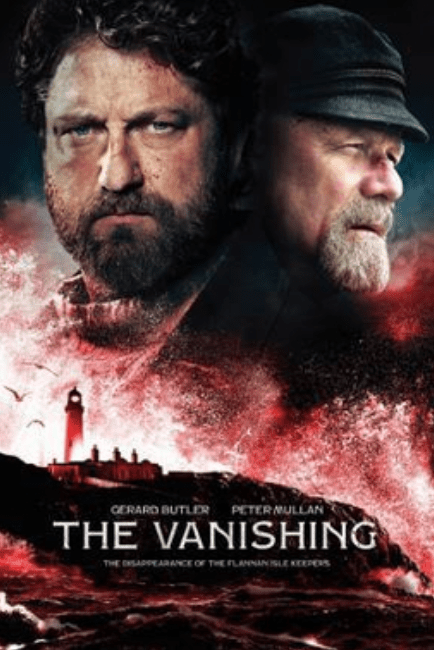

As for my plan to write a mystery, well, it’s been done and done again as far as Eilean Mor is concerned. The disappearances were included in episodes of Dr. Who, Genesis wrote an entire freaking song about it and there’s even a 2018 movie called The Vanishing with Gerard Butler.

So I might write a mystery about Liam’s story at Eilean Glas instead. A psychological thriller with lots of family drama and insanity from being trapped in a remote location with scarce resources, but also there is a sea monster and the ghost of a crazy saint and a chapel with a dog in it.

After story time at the lighthouse (Scots truly are natural storytellers), half of us headed back to the van and the rest completed the loop hike along the coast – the bog factor was off the charts which reminded Liam about that one time he had to pull a guest out of a sucking bog that was basically Scottish quicksand. We also happened upon the skeletal remains of a sheep. Don’t worry, it was all fine. As was the remarkable scenery. The red you see is water-logged sphagnum moss. More about that later.

Liam was a master at identifying plants and mushrooms along the trail, and on this hike he showed us some white spidery reindeer moss (which is actually a lichen). Pro-tip: if you ever find yourself walking for days across a frozen Norwegian tundra whilst on a secret mission to stop Hitler from gaining access to heavy water (a byproduct of fertilizer production that could be used to develop nuclear weapons), you must locate a reindeer. Of course, you need to kill the reindeer (sorry) for the meat and maybe to crawl inside the carcass for warmth, but also you can eat the reindeer moss in their stomachs as it is partially digested and thus more palatable for humans – and happens to be a vital source of vitamin C.

It is perhaps understatement to say that a mind-boggling set of circumstances had to exist to prevent Germany from developing and deploying a nuclear weapon before we did, and the seemingly innocuous hero known as reindeer moss could have been one of them.

Speaking of Nazis and nuclear weapons, I’ll just take a moment to drop a plug for Oppenheimer and this Oscar-worthy brilliant performance.

We ended our rather splendid, if water-logged day with a tour of Harris Distillery, the first (legal, ahem) distillery in Harris. It was opened and commenced production in 2015. Considering how long it takes to make and release whisky, the distillery did an excellent marketing job during what ended up being an eight-year interim period that included COVID. The BBC produced a documentary about their story, they held local and virtual ceilidhs and turned the distillery into a community gathering space. By 2017, the distillery had welcomed 144,000 visitors, including Prince Charles.

Also, like many Scottish distilleries, Harris makes a gin which provided income to hold them over since whipping up gin is a snap. While Botanist is probably the most well-known artisanal whisky-distillery crafted Scottish gin in the States, made by Bruichladdich on Islay, the behemoths, Hendrick’s, Gordon’s and Tanqueray – are also made in Scotland. The Harris gin is very, very tasty and was a smashing success from the jump. Its botanical of note is local sugar kelp seaweed (two tons collected by 2017) along with juniper, coriander, angelica root and cassia bark. It’s sold in a beautiful and distinctive ridged blue tinged bottle which won a Gold Award at the World Gin Awards in 2021 and is used as a table water bottle everywhere you look.

In yet another fun coincidence – Harris at last released its first whisky while we were there, the Hearach, which is Gaelic for a resident of Harris. And let me tell you, the entire island was utterly and completely stoked. We didn’t go anywhere the Hearach wasn’t offered up with a tinge of pride and excitement. The restaurant we had dinner on our final night, Flavour, which features just one seating, a tasting menu and an open kitchen, included the whisky in every single course and someone from the distillery was there to chat with us. The distillery has had a positive impact on the island economy, both in terms of tourism and its employment of local young people. It was created from the ground up as an integrated member of the Harris community. You love to see it, and you can definitely feel it.

The whisky is good, selling like hotcakes (I love that the first whisky release was 1,916 bottles, one for each resident of Harris), and the tour was fascinating. Every aspect of the distillery, the design, the materials, all of it – was carefully thought out and is related to Harris and its people. Many family members are involved with the company – and many women. And it’s the first distillery in my experience where they offer guests a taste of “pure spirit,” the clear liquid you see in the spirit safe – baby whisky before it’s casked and aged. Let me just say the alcohol content is hiiiigh.

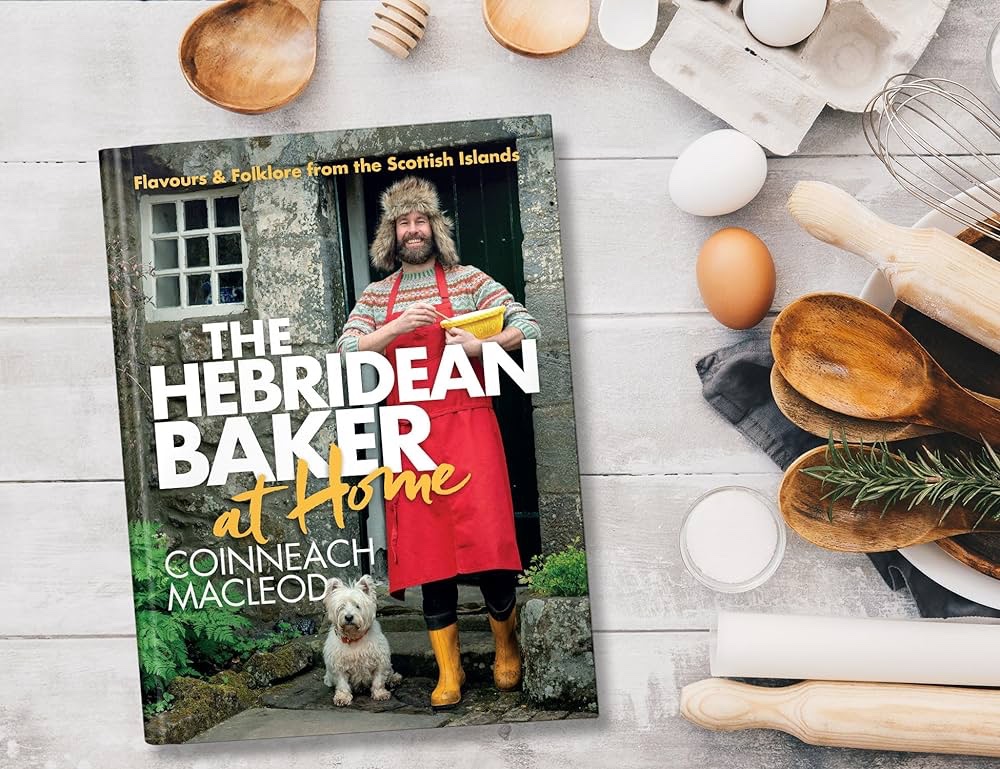

Are we tired of fabulous coincidences? No? Well – as it turns out the world-renowned, gorgeous and utterly charming Hebridean Baker happened to be at the distillery that day (actually Liam rearranged our schedule to accommodate this) signing his new cookbook, his third, which hasn’t yet been released in the States. His name is Coinneach MacLeod (told you) and he had recently returned from a tour of the States and is heading out again next year. Two of my travel companions met him recently at the Grandfather Mountain Highland Games in North Carolina, and he was genuinely delighted to see them again. His cookbooks are not only filled with scrumptious recipes with a Scottish flair, but lots of stories and tales, many wonderful photographs of the Hebrides, its residents, his west highland terrier Sonnach and his partner Peter.

The following day was probably my favorite, Hebridean Baker notwithstanding, mostly because it was like a fantasy novel crossed with a Disney film, where our intrepid group were the only souls in existence – so maybe also a dash of post-apocalyptic adventure. We drove to one of the most well-known beaches on the west coast of Harris called Hùisinis, where a person could easily spend the entire day staring out to sea and pondering life’s big questions.

And we happened to run into some highland cattle on the drive there. These iconic beasts make tourists completely lose their minds. By this point I’ve seen a fair few of these lovely creatures during my travels but I will never fail to pull over when I come across a sacred Heilan Coo Gathering. In defense of tourists (which I rarely do) Liam, born and raised in Scotland, also loves them and kept remarking on their staggeringly high cuteness level. Coos are also extremely friendly and curious and seem to know they are being photographed because I swear they pose. They do not turn tail and skedaddle like sheep or other types of cattle. They must realize that they are a four-legged embodiment of Scotland and accept their lot with grace.

And so after taking in the sands of Hùisinis our merry band of walkers headed up a cliff over the sea. We had a view of Scarp, a now uninhabited island that of course has an interesting and quirky history, this being Scotland and all. In the late 19th century the four square mile island boasted 213 residents. Fun fact, it was one of several Scottish islands where all the men gathered every morning in a so-called ‘parliament,’ to agree upon the work to be done that day. Sometimes these meetings could last several hours and this provides yet another example of why women should be in charge. The last family standing, Mr. and Mrs. Angus MacInnes and their two sons, left in 1971 on a boat. They landed at Hùisinis, their cattle swimming behind them. I like to think that they were highland cows.

Below is an undated photo of hardy Scarpians.

The remaining residents were Andrew Miller Mundy and his school friend Andrew Cox, who had moved to the island earlier that same year with his wife and baby. Several weeks after the MacInnes family left, a huge storm cut off the island and provisions ran low. Even though Scarp is only half a mile from Harris a storm can whip through that strait like nobody’s business, rendering it unnavigable due to swell and current. Mundy, in London at the time, sent a helicopter to rescue his girlfriend (romantic), a model who he later married (also romantic). And thus Scarp became a deserted island.

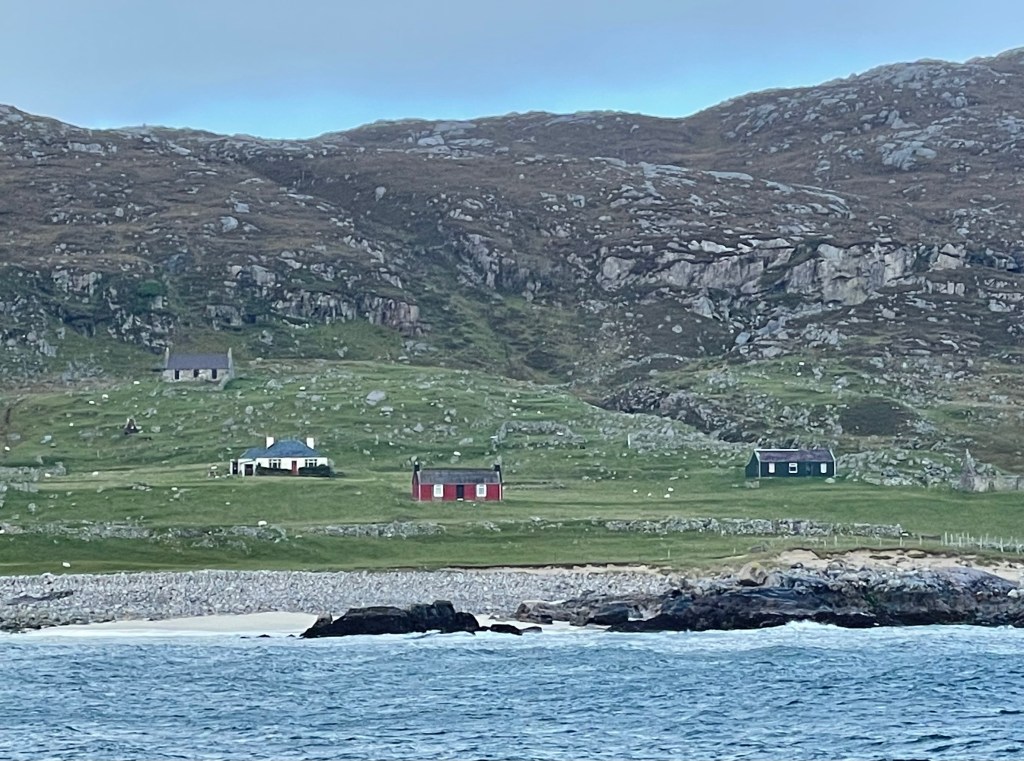

A handful of picturesque holiday homes remain that you’ll see in a minute, keeping in mind that they are only accessible via sea kayak. The island is owned by American musicologist Andrew Burr Bakewell, the founder of Harris Distillery. And I should see if he’s single.

I found a recent expired listing for a home on Scarp called The Primrose Cottage. A few tidbits: “There is no doubt the property requires significant upgrading,” and “we understand” the building had a new roof installed six years ago. There’s no septic, spring water is “available year-round” (bonus) and electricity is provided by a generator, although thankfully there is internet so what more do you need. The listing ends with “Brace yourself, Scarp is not for the faint-hearted.” There’s a restriction against using the property for “tourism/holidaymakers.” The realtors were accepting offers over £100,000. I wonder if it sold.

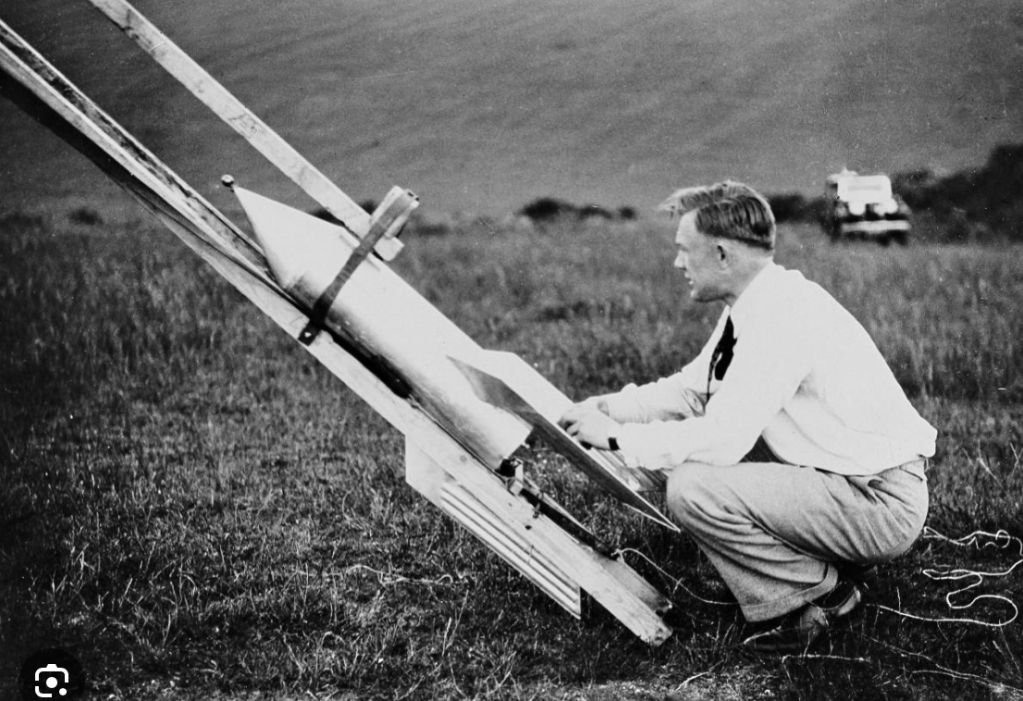

Liam also told us about another singular event for which Scarp is reknowned. In 1934 it became the setting of an exciting, if dubious, trial of the Western Isles Rocket Post (I swear). German scientist Gerhard Zucker, apparently filled with a desire to “bring the world together” via a postal-delivery system tried to send a literal rocket packed with 4,000 letters (some addressed to the King) over to Harris.

The mission failed with a dull explosion and a puff of smoke with smoldering letters scattered everywhere.

The day the rocket was launched, 28 July 1934, became known as Latha na Rocait. There’s a film about the whole affair named The Rocket Post that won the grand prize at the Stony Brook Film Festival. A play by the same name was produced in 2017 by the National Theatre of Scotland. The publicity materials state that it’s “part-play, part-gig and part-hoedown,” and is “full of humour, heart and hope for the future, it’s a tale of miscommunication, vaulting ambition and the joyous discoveries that can happen when everything goes wrong.” Indeed.

So what ever happened to Gerhard? Online sources suggest that he was deported back to Germany for postal fraud which is sort of hilarious, only to be detained by the German government for having cooperated with the British, which is more on the perilous side. Apparently Gerhard had pitched his rocket mail idea to the Germans before his Hebridean experiment. He joined the Luftwaffe, was badly wounded in 1944, and ended up working as a furniture dealer in West Germany and thus his wish to bring the world together ultimately fizzled out just like his rocket.

So, after our beautiful cliffside walk, we dropped down to another impossibly white beach, Tràigh Mheilein, only accessible via this walk. Spectacularly beautiful, deserted, and seemingly stretching on into forever. Gorgeous multi-colored rounded stones were everywhere, evidence of the complicated geographical history of the island. The weather changed approximately five million times as we meandered down the beach. Rain pants off, rain pants on, sand everywhere. Rainbows, dark clouds, blue sky, wind, no wind. The beach was framed by the Strait of Scarp with distant Atlantic views on one side and green rocky hills on the other. The water constantly changed color and character along with the weather. A few quintessentially Hebridean houses sat like lonely sentinels across the water on Scarp.

After a hasty picnic lunch in a sheltered area behind some rocks, we turned away from the water and climbed up onto a ledge where a huge expanse of bright green stretched out before us. It was like stepping through a portal into another world. There was no trail per se, we just traversed its expanse like we were in the Sound of freaking Music, only with the ocean behind us and below and mountains and lochs ahead. Each of us exclaimed something along the lines of holy crap how is this a place that exists. The well-traveled Liam shared that it was his favorite spot, maybe in the world.

We walked along this loch, marveling at the lonely white house on the other side (a deer stalking cottage leased by a nearby estate) when suddenly a green field studded with white rocks opened before us – and hundreds of bunnies scampered in a flurry, disappearing down into their warrens. It was – ridiculously magical. Of course I couldn’t snap a photo in time, but they were just here:

We walked a bit farther and then spotted a huge herd of red deer up on the ridge – and they kept a steady eye on us as we climbed up toward them, finally dispersing as we grew too close.

The views back over the loch and bunnyville were fab.

As we crested the ridge and headed back to the sea a juvenile sea eagle soared overhead, tracing giant, graceful circles in the sky. While commonly referred to sea eagles, they are officially called white tailed eagles. They boast a seven foot wing span and are the largest bird of prey in UK. They almost became extinct in early 20th century, mostly due to death-by-landowner. These were wealthy owners of vast estates who were protecting their game birds, which they keep stocked for shooting parties of hunter types who have paid massive sums for the experience. I mean seriously this is not at all vital or even interesting and why is this even a debate. Anyway thanks to modern conservation efforts and breeding programs in Scotland and England, the sea eagles have been making a comeback. Unfortunately they remain endangered as gamekeepers who work on these aforementioned estates are still poisoning them. In response, the Scottish government has pulled shooting licenses in the hope that this would reduce these crimes. Unfortunately cases are hard to prove unless one finds the bird and runs a tox screen within a certain period of time and can pinpoint the culprits. Surely, the majestic sea eagles must prevail over such waste and stupidity.

A few snaps from our walk down the ridge:

We had a lovely afternoon tea on Hùisinis beach before hopping back in the van. As we drove away we passed the coos again and Liam obligingly stopped in the middle of the road so we could bid them a fond adieu. One of them walked over to my window in greeting, politely requesting a head scratch, which I gladly obliged. His/her horns banged against the side of the van, so apologies to Wilderness Scotland.

We finished our day by hiking down Glen Meavaig, a wildlife refuge featuring the North Harris Eagle Observatory, built to provide a sheltered spot for viewing a resident nesting pair of golden eagles. Sadly we did not see them. Apparently the Universe felt that we had seen enough magical creatures for one day.

I’ll leave you with a very cool fact about North Harris. It was purchased by the community in 2003, and its 25,900 acres make up one of the largest community owned estates in Scotland. The North Harris Trust, which manages the land on behalf of the community, has an open membership to all residents and is run by a board of locally elected volunteer directors. Very cool.

Julie. Looking forward to tomorrow and more stories of your trip. Wh

LikeLike