The next morning dawned brilliantly sunny and so was perfect for an ascent to Shetland’s highest point. Ronas Hill reaches a height of 1,480 feet and is a lovely walk with a very gradual slope. It overlooks Yell Sound, the North Sea, the Atlantic and even offers a wee peek at Fair Isle, the most distant of Shetland’s islands. This being Scotland, there’s a Neolithic chambered cairn at the top, which is unusual as cairns usually weren’t built on summits.

On our way up the hill Barb and I were startled by a sudden rustling of wings as we flushed a plover. We watched her fly away from us, skimming over the ground and flying as though she was under the influence. Whereas I was all, oh no that poor bird, Barb knew what she was seeing and started searching for a nest, as she knew the plover was trying to lure us away with a quite convincing act of being injured and thus easy prey.

The ascent was barren, tundra-like and largely featureless, but we came upon an oasis midway up. We stopped at a beautiful wee loch which was brimming with squiggly tadpoles.

The summit, as advertised, offered grand 360 degree views, the aforementioned Neolithic cairn, and a trig point, which you are legally required to touch, otherwise your climb did not officially happen.

The walk was a brilliant way to start the day. After some down time at the hotel and a lovely dinner, we met in the lobby and drove to catch a boat with a 10:30 pm launch time to visit the island of Mousa (“Mossy Island” in old Norse), featuring an Iron Age broch and other ruins. Uninhabited since the 19th century, it is now a nature reserve. The island is 1.5 miles long and 1 mile wide, and it is known for its breeding European storm petrels. They are best seen after dark, as that is when they return to the broch after a day spent gallivanting around doing petrel things. They wait until dark to avoid predators, especially the notorious jerk birds called great skuas, locally known as bonxies.

Mousa is the home of around 6,800 breeding petrel pairs, which is 8% of the British population and 2.6% of the world’s. I was also looking forward to properly experiencing the beginnings of “simmer dim,” which is what Shetlanders call the weeks of midsummer when the sun sets, but the situation never progress beyond twilight. We were a few weeks shy of maximum dim, but still something I hadn’t yet experienced. I have no problem sleeping in the light so I had been snoozing through it, much like I had done during the Northern Lights earlier in my trip. Sigh.

We arrived at the dock at the appointed hour.

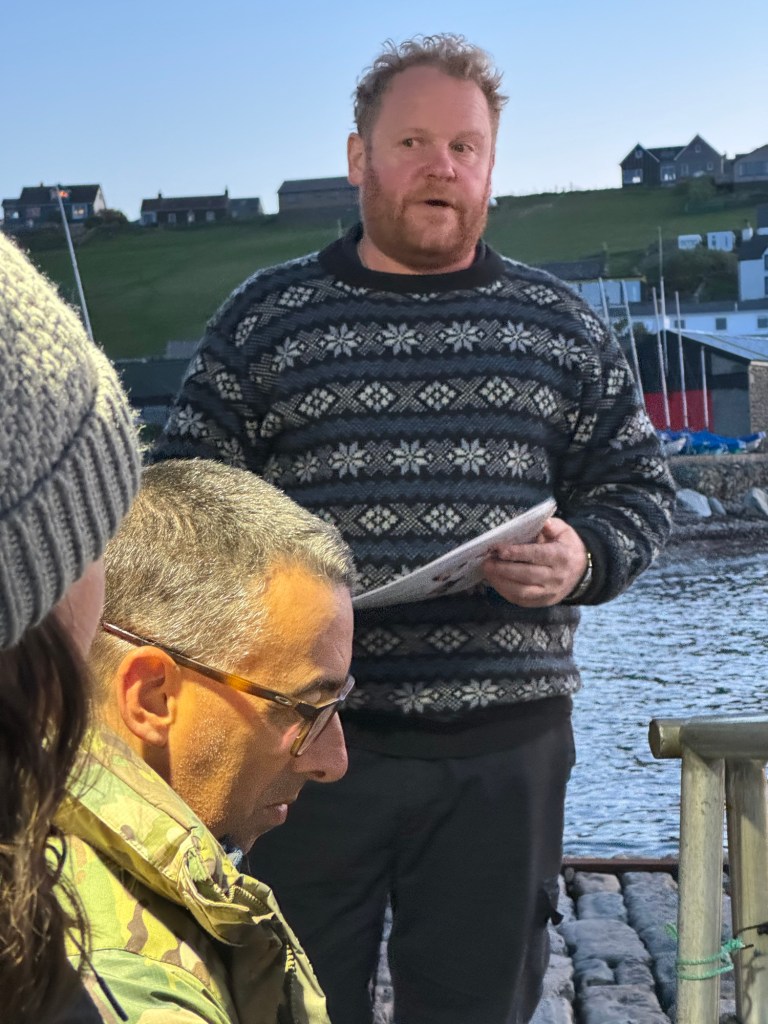

The boat is captained and crewed by father and son comedy team Rodney and Darron – who don’t look related at all. ;o) I forget which is which so for our purposes let’s say Rodney is the dad and Darron the son. They operate their boat all summer, taking folks out at night for the petrel experience and during the day to see all the other ruins on the island. They have deep roots in the area. Rodney’s grandfather was a lighthouse keeper, running the lighthouses at both Mousa and Sumburgh.

On the way, we stopped and picked up a couple from a lovely wooden boat moored off the coast of Mousa which involved some pretty fancy boat maneuvering.

Once we landed, we were given palm-sized lights that had been removed from headlamps. Rodney and Darron gave us the petrel rules, which were basically they don’t like white lights but they don’t mind red, so we practiced activating both. Along our 15 minute walk to the broch Rodney regaled us with a history of the island’s human inhabitants with Darron helpfully piping in with asides, embellishing his dad’s stories.

One tale was about the former residents of the Haa, a ruin of a home overlooking the broch. James Pyper, a Lerwick merchant, bought the island and built the Haa in 1783. Rodney winked at us and said, “James built the house for his wife Janet Gray, to keep her from the ‘drraank,'” trilling the r like a boss, at which point Darron lifted his head from his phone and clarified, “alcohol.” Upon Janet’s demise (one wonders how) James next married Anne Linklater who lived alone on Mousa for 25 years after his death. Well, not quite alone, according to the records she had three young servants and a mysterious “lodger” named David Kay. Good for her I say.

We briefly stopped in front of a bench that Rodney built, as Darron said, “with his own hands,” to mark the 60th parallel. They were both very proud of it.

Malachi Tallack wrote a book published in 2015 called 60 Degrees North, which recounts his circumnavigation of the earth along this latitudinal line, starting from Mousa and passing through Greenland, Canada, Alaska, Siberia, St. Petersburg, Finland, Sweden and Norway. Rodney allowed as how he had written to Tallack requesting that he visit and have his photo taken on the bench. Much to his chagrin, Tallack has not yet given him the courtesy of a reply.

The walk was, in a word, spectacular. In addition to the ongoing twilight, the nearly full moon was kind enough to position itself in an entirely picturesque manner over the broch.

The 2,000 year old broch is the best preserved Iron Age fortification in the British Isles. It’s one of a pair of broths guarding Mousa Sound, and may be part of a chain of them, visible from one another as Lord of the Rings style beacons.

As we stood around the broch, Rodney continued with his stories, a treatise on petrels, and editorial commentary about the automation of lighthouses, “They took something that’s been working fine for 200 years…,” but I was distracted by bats flapping around over our heads, which were in fact storm petrels returning home to roost. They are very small birds, there wasn’t a lot of light and their flight patterns were erratic and swoopy. Darron said on his last trip he was chatting up a guest, and asked whether she had seen the petrels. She said, “No, but I’ve seen quite a few bats,” which he found hilarious.

At last it was time to enter the broch. Rodney warned us again about shining white light on the petrels and said there was a spiral staircase inside that was the oldest continuously in use staircase in UK. He added a semi-disclaimer, to-wit, “I haven’t heard anyone tell me any different so until I do I’m going to keep saying it.” He told us to be careful and hold onto the rail, suggesting that we navigate the staircase sideways, and added that we could use the white light for “your own safety,” but if we saw a bird we must change it to red.

So we walked into the dark broch. On first glance toward the staircase, my reaction was oh hell no but then for some reason I crossed the uneven stone floor of the broch and started climbing stairs that made the Wallace Monument’s seem like Tara’s sweeping grand staircase in Gone With the Wind. I feel pretty confident that this is indeed Ye Oldest Staircase. In the States it would have been roped off from tourists hundreds of years before.

There was indeed a wrought iron bar bolted into the side of the stairwell. On average, the stairs were maybe four inches wide with some less and some more. And being inside the best preserved broch in the UK it was extra double dark in there.

I shined the white palm light down at my feet with one hand and gripped the iron bar in the other, leaned back and sidestepped up the uneven shallow steps that weren’t wide enough to support the entire width of my foot. I jettisoned the instruction that if I saw a bird I was to switch the light to red because unless a petrel alighted on my foot, it wasn’t going to happen.

When at last I emerged onto the roof of the broch, the view made me forget the perils of the climb.

That is, until I decided to come down. Which was worse as far as peril level was concerned. Barb was behind me and said in my ear with her fabulous Kiwi accent, “If I take you out it’s going to be sudden and spectacular,” and so the two of us made our descent with hysterical laughter echoing through the broch which I’m sure the petrels weren’t stoked about but probably better than a white light.

Speaking of petrels, you might be wondering what that experience was like. Well I’ll level with you. While the idea of it was very cool, the experience of it was like seeing bats flapping around outside an ancient stone wall in very dim light. I didn’t see any petrels inside the broch because the moon’s light didn’t penetrate the walls and my gaze was affixed to my feet an ongoing effort to not die. Richard approached as we waited to walk back to the boat and said, “To be honest I’m more interested in the archaeology than I am in these birds,” which was pretty much aligned with my point of view.

What a seriously wonderful experience though. We walked back to the boat in silence and enjoyed a beautiful ride back to the dock, dropping off our friends at their wooden boat along the way. We left for the hotel at about 1:00 am. The eastern horizon was glowing with the light of an impending dawn.

On the drive I shared the above photo with my friend Drew in New York who can monitor my location on FindMy. He sent me this:

As Barb would say, “This was the best day.”