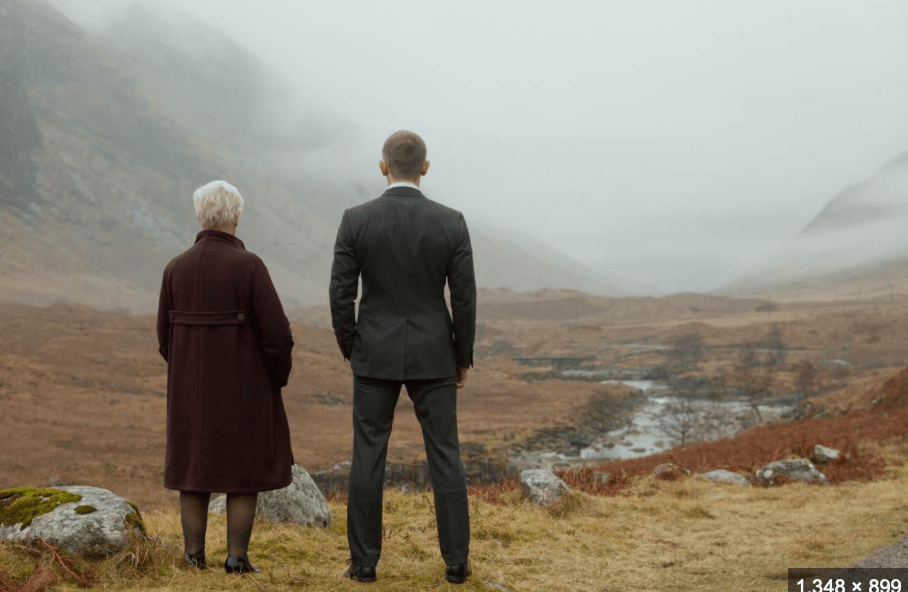

I spent today, my last in Glencoe, with the Three Sisters. As it came to a close, I left the glen and drove to Appin to find a fairy bridge and have dinner at a haunted pub on the shores of Loch Linnie with a castle view. These are the kinds of activities you can throw together in Scotland.

We have Three Sisters in the Central Oregon Cascades known as South, Middle and North – not the most original but people were probably tired from crossing the Oregon Trail and not feeling particularly creative. In Glencoe the sisters are known as Beinn Fhada (long hill), Gearr Aonach (short ridge) and Aonach Dubh (black ridge), all a part of a ridge known as Bidean Nam Bian, meaning “peak of the mountains.” Also more descriptive than creative but the Gaelic adds zhuzh.

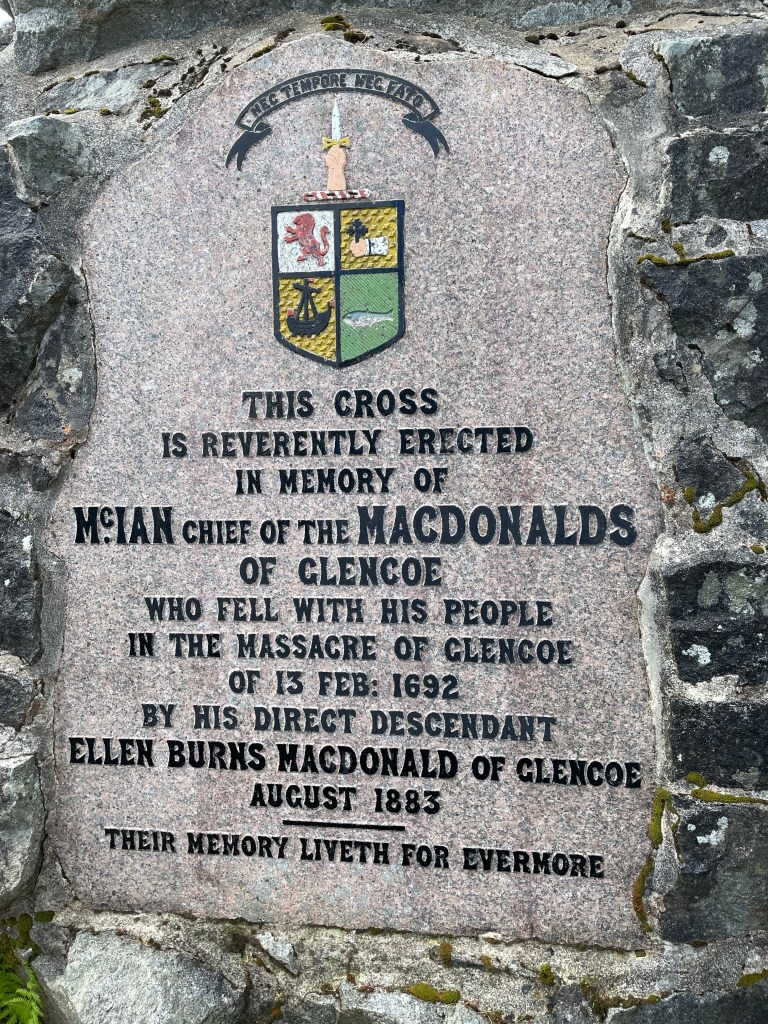

Morning commenced with a hike called The Lost Valley, or Coire Gabhail (pronounced “corry gale”), located between the easternmost sister and the middle one. The valley was not lost but a secret, and hard to access. It was used by the MacDonalds as a hiding place for rustled cattle (the family business) and it served as a refuge for those who escaped being murdered during the 1692 Massacre of Glen Coe. Although not really a refuge, as it turned out, since more folks froze to death after escaping than were killed by members of the Campbell Clan, aka rudest guests ever. Ah, but you know all about the Massacre because you read my previous blog and memorized all the facts.

The hike featured some challenging moments and the idea of urging a herd of cattle up this canyon seems completely insane but back in the day maybe cows were tougher. And fleeing up into the canyon in the snow and dead of night with no light source sounds even more impossible.

While relatively short, the hike is a gnarly enough to merit installed hiking accessories along the trail which is not much of a thing in Scotland. There are steep metal steps, handrails, and metal cables drilled into rock next to a sheer slope so you can pull yourself up. Another bit of perilous business leaves you to your own devices as there was simply nothing for it. It’s a section of smooth, steep rock with a fun drop off down one side. Walkhighlands says, “the scrambling is pretty straightforward but some may find the situation airy.” Meaning too much air and not enough rock I guess? To make matters more exciting, the rock has been polished to a high sheen due to years and years of rear-end polishing thanks to all the butts that have slid down it. If you find yourself in Glencoe, do not attempt this hike if it’s been raining. This would be my advice.

And goodness gracious me it was beautiful.

The Lost Valley itself was like a moonscape. Much larger than I expected, it could hold a fair few cattle. And by that I mean easily hundreds.

The descent was easier even with my knees not being fully stoked. And there is often a piper in that particular parking lot, as there was this day, and so my return was scored with a triumphant soundtrack. That’s right, I thought. I did it and now the pipes are playing me home.

By the way, McRaggie plays entrance music whenever I open the car door. More orchestral than bagpipes. It makes me smile every single time. And I play the NYTimes mini-crossword for the little jazzy piano tune it plays when you complete it. Maybe I should speak to a therapist about this.

Buoyed by not dying, I thought another walk was totally reasonable and so stopped for a quick ramble to visit Ralston’s Cairn. And admittedly I never would have known it existed without Instagram. Ralston Claud Muir was a train driver on the West Highland Line and loved to hike in the hills of Glencoe. He sadly died unexpectedly at 32 and his friends and family erected a wee cairn and spread his ashes there. It’s a gorgeous spot, off the trail and a little hard to find, which he probably would have appreciated. I suspect other ashes have been surreptitiously added over the last twenty plus years.

I planned to head to nearby Appin for dinner, and had recently learned there was a lovely walk in the area. It’s in Glen Creran Forest and features a 500 year old bridge known more specifically as, of course, the Fairy Bridge.

The hike is at the end of a single track road along Loch Creran lined by fabulous old homes with brilliant landscaping, azaleas in full bloom. Saw lots of ladies out and about tending their gardens. And so many border collies.

Arriving at the small car park, no sooner had I turned off the ignition than I was unexpectedly accosted by a blonde Norwegian woman who told me with great certainty tinged with agitation that this was the wrong car park. “I’m sorry?” “Are you going to the Fairy Bridge?” “Yes.” “Well, this is the wrong car park. We followed navigation but there’s no cell service here. Do you have different navigation?”

Forgive me, but I had absolutely zero interest in suggesting we should walk together even though I had downloaded the map and didn’t need cell service and I’ll fight anyone who says Walkhighlands.com would ever lead you to the wrong car park.

Plus I had to pee, so.

“Well, I’m just going to go for a little walk anyway to stretch my legs I think,” I said, trying to make her go away. She wandered off and then reappeared before I could lace up my boots, and shared more late breaking news. “I went up there,” gesturing vaguely behind her, “and there’s a board, and there’s a way you can get to the Bridge from here but it’s a detour (thus implicitly sticking to her wrong car park theory) so I’m sure you’ll find it.”

Does she want me to ask her to come with? Or is she leaving? If I can find it, why can’t she? What is happening? I saw she had a dude in her car because one of his legs was sticking out of the door and she kept going back and consulting it. I’m imagining he was rolling his eyes at this whole Fairy Bridge ordeal that she coerced him into (I mean to be fair how many men would be like, yes please, let’s go see the Fairy Bridge). Also he was no doubt exhausted by the disproportionate drama that invades much of his life due to this woman of certitude.

When she wandered off again to consult the leg I seized my chance, vaulted out of the car and hauled ass up the steep trail.

The real revelation on that walk, though, was not the bridge but the bluebells. They completely blanketed both sides of the trail along the entire walk. I couldn’t quite capture their beauty. Some things are just better in real life.

Not easy to outdo the bluebells but the Fairy Bridge was relatively nifty. And for the record, it wasn’t part of a “detour” or whatever. Walkhighlands remains invincible.

Coincidentally, the BBC just ran a piece on the couple who created (in 2006) and continue to maintain that invaluable hiking resource, Helen and Paul. You might enjoy taking a peek: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c72py4xg2w4o

I walked along the road for a bit on the way back to the car and tried to imagine what it must be like to live there…..and came to the conclusion that it wouldn’t be a hardship.

I should also mention, as it ties in beautifully with a story you’re about to hear, that I came upon a signpost along the Fairy Bridge trail which referenced nearby Glen Ure and included quite a detailed history. Back in the 1700s Colin Campbell was the Laird of Glen Ure and you might jot that down as we rejoin our pal McRaggie in the parking lot and head to dinner at the Old Inn.

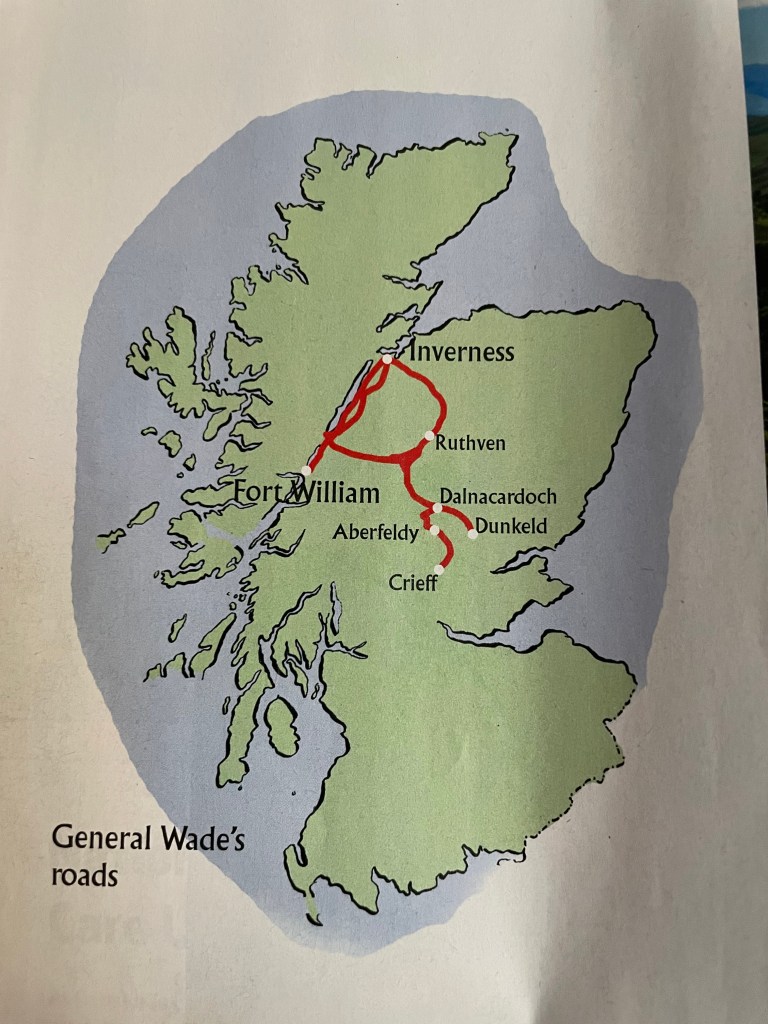

Appin, on the shores of Loch Linnie, is interestingly central – it’s 100 miles from Glasgow, Edinburgh and Inverness. The Old Inn, I had heard, is allegedly haunted by the ghost of a Highlander wrongly hanged for murder. Excellent. The pub was established in 1670, closed in 1880, and Jim Mulligan bought the property in 2016 and gamely undertook a $1.2 million restoration project. Jim believes he has identified the ghost. He thinks it’s James Stewart, known as “James of the Glen.” He was hanged for shooting Colin Campbell, “The Red Fox,” (honestly these monikers) in Appin in 1752.

This is what happened. Campbell, a government agent, was shot in the back while collecting rents from members of the Stewart family whose estates had been forfeited to the British government due to the clan’s support of the 1745 Jacobite rising. Upon being shot James allegedly informed everyone, “Oh, I am dead,” or words to that effect, and his alarmed compatriots observed a shadowy figure running away into the hills. George II’s government was jittery after the ‘45 and thought these could have been the first shots fired in another rebellion and so London sent word to do whatever was necessary to handle the situation, preferably making an example of the perpetrator. Shut it the hell down, in other words.

Our future ghost James, the most powerful Stewart in the area, had led local opposition to the evictions. In other words, he was a perfect mark. And so he was arrested and charged with aiding and abetting the murderous act of his foster son, Allan Breck Stewart. (Sounds odd but sons of clan members commonly lived under the protection of the clan chief). Allan fought on the Jacobite side at Prestonpans and so was another obvious scapegoat, although he wisely fled to France and so was beyond the reach of government authorities. After a four day trial, with most of the jurors being (ahem) Campbells, the verdict was a foregone conclusion for our poor James.

He was hanged near Glencoe (wee reminder here that the Campbells were also the bad guys in the Glencoe massacre sixty years earlier) and, dear readers, avert your eyes. His body was left dangling from the gallows under guard for three years. Under guard. Lest you think your company piffles FTE on unnecessary tasks.

It was known locally that neither Allan nor James were involved in the murder. You can see why James, in particular, would be super pissed about the chain of events but it’s hard to imagine that he’d live out his ghostly days haunting a renovated pub in Appin. Getting his sweet, sweet revenge by bothering its staff.

Ah but our story doesn’t end there. Many stories about Scottish history that have seeped into popular imagination are due to either Walter Scott or Robert Louis Stevenson wandering through the past in search of material. They wrote accounts about historical incidents which launched these mostly forgotten and not widely known events into worldwide notoriety. They were, in essence, the 24 hour news cycle of the early 1800s and had much to do with romanticizing Highland culture.

In this case, a hundred years after the murder, Stevenson’s father found, in Inverness, a slim volume called Trial of Stewart. He thoughtfully purchased it for his son who was writing a book on the history of the Highlands (instead of designing and building all the lighthouses in Scotland, see previous blog entries about this family).

As a result of this gift, our man Allan Breck Stewart, even though he managed to escape history for a time, became the lead character in “Kidnapped,” Stevenson’s book that dramatized the Appin murder. Thus Allan, who played quite a minor role in the Appin murder, became immortalized a hundred years after his death.

Also, now I have to read Kidnapped.

So not to cast aspersions on our friend Jim the pub owner, but his sly assertion that the ghost of the Appin Inn is James of the Glen – because he drank in the pub (as did everyone) and because some evidence for the trial was presented in the Inn’s back room, is clearly more about publicity than reality. But I mean good for him, if a famous ghost gets him butts in seats, all to the good.

Speaking of reality, let me be clear that this does not mean the pub is ghost-free. Staff have been creeped out by rattling glasses, pans flying through the air and chairs falling over. Mysterious footsteps in an empty upstairs room and shadowy ghost figures have caused people who aren’t paid enough for this crap to turn out the lights and skedaddle. Most creepily a nonbelieving staffer, alone at night, said, “The fire suddenly went down and the glasses in the gantry started rattling. We had a St. Andrew’s flag up above the gantry and, when the glasses stopped, the flag started billowing. I looked round and a chair was on its side.”

Yikes.

The last thing you should know about the Old Inn at Appin is that the food is excellent – they specialize in locally sourced grass fed steaks, which I ordered. So, dear reader, I have my first (confirmed) experience of eating a Highland Coo. Don’t judge. I feel bad about it.

The pub serves a DELICIOUS black pepper cream sauce to go with their steaks and chips. It’s a hefty portion served hot in a ramekin. I was contently dousing a bite of coo when something fell in with a splash. I stared, taking a second to clock that a dreaded yellow jacket had swan dived into my ramekin. I harbor quite a bit of hate in my heart for the aggressive meat-eating little dickheads, their families, and all they represent. I scooped it up into my spoon and flicked it onto the table where it staggered around drunkenly, coated in black-flecked white goo. My first thought, and I’m allergic to yellowjackets mind you, was that I need to have my cream sauce replaced as soon as possible. I waved down the waiter and explained – he nodded and whisked the ramekin away. Shortly thereafter the bartender brought me a new one filled to the brim and steaming hot. I dismissively gestured at the bee, still carving a drunken path around the table, he nodded, disappeared and came back with a paper towel. The bee found its footing and obligingly climbed onto it and he took it outside. He told me later he tried to wipe the peppercorn cream sauce off the bee but could not give me a solid prognosis as as to his recovery.

“He’ll probably be popular with the other bees,” I suggested, possibly batting my eyelashes. I mean seriously, my hero. An entire new ramekin of the best sauce in the world and a bee whisperer.

After basically drinking my weight in sauce, I wandered down to the Loch and snapped a few backlit photos of Castle Stalker. It’s privately owned but they do arrange tours and take people out there by boat during the summer.

And what is its history, you ask? We are at the end of our entry and possibly our tolerance for obscure Scottish history, so allow me to simply share the nutshell version. It was built in 1320 and many clans have passed through its halls since. There have been MacDougalls, Stewarts, King Bruce, the Lord of Lorn, a MacLaren, MacCouls, MacDonalds, Campbells, a dude called Donald of the Hammers, more than a few murders, battles, cattle rustling, a passage of title via a drunken wager and also a besiegement or two. It was occupied by government forces after Culloden and served as a local center for the surrender of weapons. The roof collapsed at one point and the owners didn’t bother repairing it because no roof meant no taxes. At last, in 1965, Lt. Colonel Stewart Allward purchased it from a Stewart and oversaw a ten-year restoration. It’s now fully habitable.

The day’s adventures having at last come to a close, I headed back to Glencoe for one more night. It was such a beautiful evening I drove down Glen Etive and gave the Bookel a proper goodbye.